在类Unix操作系统中,管道(Pipeline)是一系列将标准输入输出链接起来的进程,其中每一个进程的输出被直接作为下一个进程的输入。

目录

- 系统调用 fork

- 管道

- 示例

- 管道的读写

- 读管道

- 写管道

- 管道的特点

- 管道的局限性

- 双向管道通信

- 参考

系统调用 fork

在linux系统中创建进程有两种方式

- 一是由操作系统创建。

- 二是由父进程创建进程。系统调用函数fork()是创建一个新进程的唯一方式。

fork()函数通过系统调用创建一个与原来进程几乎完全相同的进程。

- 系统先给新的进程分配资源,例如存储数据和代码的空间。

- 然后把原来的进程(父进程)的所有值都复制到新的新进程(子进程)中,只有少数值与原来的进程的值不同。

- Linux的fork()采用写时拷贝实现,只有子进程发起写操作时才正真执行拷贝,在写时拷贝之前都是以只读的方式共享。这样可以避免发生拷贝大量数据而不被使用的情况。

fork是Linux系统中一个比较特殊的函数,其一次调用会有两个返回值。在fork函数执行完毕后,如果创建新进程成功,则出现两个进程,一个是子进程,一个是父进程。如果失败返回值是1。

- 在子进程中,fork函数返回0。

- 在父进程中,fork返回新创建子进程的进程ID。

因此我们可以通过fork返回的值来判断当前进程是子进程还是父进程。

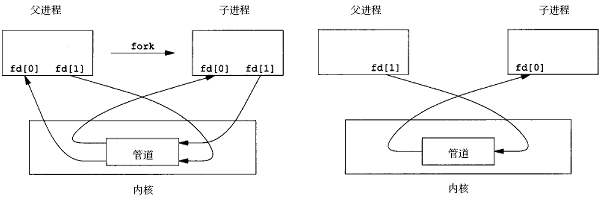

管道

Linux中,每个管道允许两个进程交互数据,一个进程向管道写入数据,一个进程从管道读出数据。Linux并没有给管道定义一个新的数据结构,而是借用了文件系统中文件的数据结构。即管道实际是一个文件(但是与文件并不完全形同)。

操作系统在内存中为每个管道开辟一页内存(4KB),给这一页赋予了文件的属性。这一页内存由两个进程共享,但不会分配给任何进程,只由内核掌控。

示例

Linux pipe手册中的例子

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

| #include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int pipefd[2];

pid_t cpid;

char buf;

if (argc != 2)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s <string>\n", argv[0]);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

if (pipe(pipefd) == -1)

{

perror("pipe");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

cpid = fork();

if (cpid == -1)

{

perror("fork");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

if (cpid == 0)

{

close(pipefd[1]);

while (read(pipefd[0], &buf, 1) > 0)

write(STDOUT_FILENO, &buf, 1);

write(STDOUT_FILENO, "\n", 1);

close(pipefd[0]);

_exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

else

{

close(pipefd[0]);

write(pipefd[1], argv[1], strlen(argv[1]));

close(pipefd[1]);

wait(NULL);

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

}

|

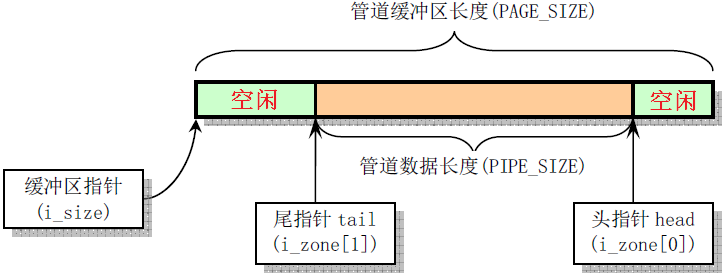

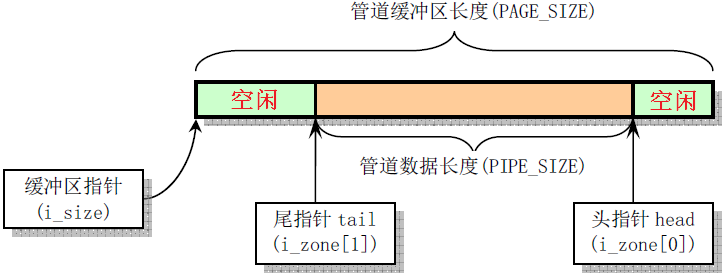

管道的读写

- 读管道进程执行时,如果管道中有未读数据,就读取数据,没有未读数据就挂起,这样就不会读取垃圾数据。

- 写管道进程执行时,如果管道中有剩余空间,就写入数据,没有剩余空间了,就挂起,这样就不会覆盖尚未读取的数据。

读管道

对于读管道操作,数据是从管道尾读出,并使管道尾指针前移‘读取字节数’个位置。

Linux 0.11 源码

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

|

int read_pipe(struct m_inode * inode, char * buf, int count)

{

int chars, size, read = 0;

while (count>0) {

while (!(size=PIPE_SIZE(*inode))) {

wake_up(&inode->i_wait);

if (inode->i_count != 2)

return read;

sleep_on(&inode->i_wait);

}

chars = PAGE_SIZE-PIPE_TAIL(*inode);

if (chars > count)

chars = count;

if (chars > size)

chars = size;

count -= chars;

read += chars;

size = PIPE_TAIL(*inode);

PIPE_TAIL(*inode) += chars;

PIPE_TAIL(*inode) &= (PAGE_SIZE-1);

while (chars-- >0)

put_fs_byte(((char *)inode->i_size)[size++],buf++);

}

wake_up(&inode->i_wait);

return read;

}

#define PIPE_HEAD(inode) ((inode).i_zone[0])

#define PIPE_TAIL(inode) ((inode).i_zone[1])

#define PIPE_SIZE(inode) ((PIPE_HEAD(inode)-PIPE_TAIL(inode))&(PAGE_SIZE-1))

|

写管道

对于写管道操作,数据是向管道头部写入,并使管道头指针前移‘写入字节数’个位置。

Linux 0.11 源码

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

|

int write_pipe(struct m_inode * inode, char * buf, int count)

{

int chars, size, written = 0;

while (count>0) {

while (!(size=(PAGE_SIZE-1)-PIPE_SIZE(*inode))) {

wake_up(&inode->i_wait);

if (inode->i_count != 2) {

current->signal |= (1<<(SIGPIPE-1));

return written?written:-1;

}

sleep_on(&inode->i_wait);

}

chars = PAGE_SIZE-PIPE_HEAD(*inode);

if (chars > count)

chars = count;

if (chars > size)

chars = size;

count -= chars;

written += chars;

size = PIPE_HEAD(*inode);

PIPE_HEAD(*inode) += chars;

PIPE_HEAD(*inode) &= (PAGE_SIZE-1);

while (chars-- >0)

((char *)inode->i_size)[size++]=get_fs_byte(buf++);

}

wake_up(&inode->i_wait);

return written;

}

#define PIPE_HEAD(inode) ((inode).i_zone[0])

#define PIPE_TAIL(inode) ((inode).i_zone[1])

#define PIPE_SIZE(inode) ((PIPE_HEAD(inode)-PIPE_TAIL(inode))&(PAGE_SIZE-1))

|

管道的特点

- 管道是半双工的,数据只能向一个方向流动;需要双方通信时,需要建立起两个管道;

- 只能用于父子进程或者兄弟进程之间(具有亲缘关系的进程);

- 单独构成一种独立的文件系统:管道对于管道两端的进程而言,就是一个文件,但它不是普通的文件,它不属于某种文件系统,而是自立门户,单独构成一种文件系统,并且只存在于内存中。

- 数据的读出和写入:一个进程向管道中写的内容被管道另一端的进程读出。写入的内容每次都添加在管道缓冲区的末尾,并且每次都是从缓冲区的头部读出数据。

管道的局限性

- 只支持单向数据流。

- 只能用于具有亲缘关系的进程之间。

- 没有名字(有名管道是 FIFO)。

- 管道的缓冲区是有限的(管道制存在于内存中,在管道创建时,为缓冲区分配一个页面大小)。

- 管道所传送的是无格式字节流,这就要求管道的读出方和写入方必须事先约定好数据的格式,比如多少字节算作一个消息(或命令、或记录)。

- …

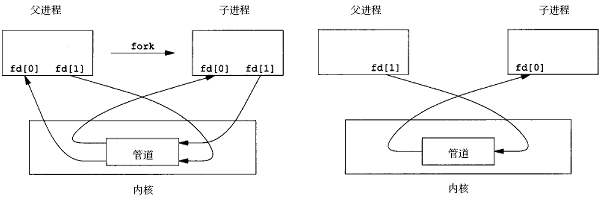

双向管道通信

- 父进程创建两个管道,pipe1和pipe2.

- 父进程创建子进程,调用fork()的过程中子进程会复制父进程创建的两个管道.

- 实现父进程向子进程通信:父进程关闭pipe1的读端,保留写端;而子进程关闭pipe1的写端,保留读端.

- 实现子进程向父进程通信:子进程关闭pipe2的读端,保留写端;而父进程关闭pipe2的写端,保留读端.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

| #include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int pipe_command[2];

int pipe_result[2];

pid_t cpid;

char buf[4];

if (pipe(pipe_command) == -1)

{

perror("pipe_command");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

if(pipe(pipe_result) == -1)

{

perror("pipe_result");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

cpid = fork();

if (cpid == -1)

{

perror("fork error");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

if (cpid == 0)

{

printf("sub: pid %d\n", getpid());

close(pipe_command[1]);

close(pipe_result[0]);

int read_status;

while (1)

{

read_status = read(pipe_command[0], buf, 4);

if(read_status > 0)

{

printf("sub: command %s\n", buf);

if(strcmp(buf, "hell") == 0)

{

write(pipe_result[1], "okok", 4);

}

else if( strcmp(buf, "exit") == 0)

{

printf("sub: exit\n");

break;

}

}

else if(read_status < 0)

{

perror("sub: read error!");

break;

}

}

close(pipe_command[0]);

close(pipe_result[1]);

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

else

{

printf("parent: pid %d\n", getpid());

close(pipe_command[0]);

close(pipe_result[1]);

write(pipe_command[1], "hell", 4);

int read_status;

while (1)

{

read_status = read(pipe_result[0], buf, 4);

if(read_status > 0)

{

printf("parent: received %s\n", buf);

write(pipe_command[1], "exit", 4);

break;

}

else if(read_status < 0)

{

perror("parent: read error!");

break;

}

}

close(pipe_command[1]);

close(pipe_result[0]);

int status;

waitpid(-1, &status , 0);

if(WIFEXITED(status))

{

printf("exited: %d\n", WEXITSTATUS(status));

}

else if(WIFSIGNALED(status))

{

printf("signaled: %d\n", WTERMSIG(status));

}

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

}

|

参考

- 《Linux内核设计的艺术》

- 《Linux内核设计与实现》

- Linux v0.11内核源码(https://github.com/karottc/linux-0.11)